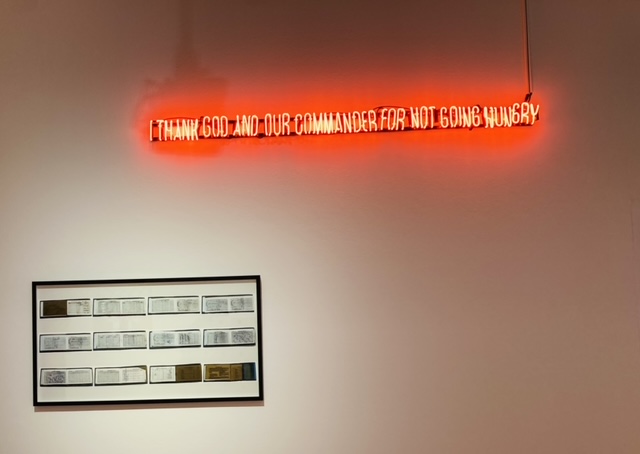

The images are installation views from exhibition: Handle With Care, Ludwig Museum Budapest, 12 September, 2023 – 14 January, 2024

Cuba is no stranger to food shortages and a lack of access to basic items. The issue has existed even before Fidel Castro’s socialistic revolution in 1959, but of course escalated right after it by, among other things, the American trade blockade, Cuba’s isolated island position and its complex political history with strong financial ties to the Soviet Union. Yet, this time, problems have reached a new level.

After Covid-19 travel restrictions and a political decision to reserve imported goods for those with access to foreign currencies, Cubans are struggling more than ever to get essential commodities and migration numbers are soaring as a result. Lines grow outside grocery stores, where people wait for hours armed with their libretas, or ration books, in hopes of buying meat, milk, eggs and bread. Many return home empty-handed.

Pharmacies are almost empty and medication is hard to come by. These days, a growing black market on the internet is one of the few places where Cubans can find commodities such as antibiotics, soap or toilet paper. Moreover, during the height of Covid-19, the government created a payment method called MLC. Basically, it is foreign money such as U.S. dollars or euros that you need to buy necessary goods in so-called MLC stores. However, since all local salaries are paid in national pesos, the only way to obtain this credit is from tourists or Cubans living abroad. Since 2019, these special shops using the convertible currency system have been established in bigger cities. They offer imported goods like hygienic products, medicine and foods such as bread, meat and pasta, but purchases require using an MLC credit card charged with foreign currencies. As a result, many Cubans can’t use the stores. Instead, they must look for the same products in local peso stores or obtain them on the black market. Both options are expensive. This change in payment method has worsened an already problematic dependency on tourism.

Today, a doctor earns around 4.000 Cuban pesos (around $30) a month, while a taxi driver can charge – but not personally make – 3,000 pesos ($25) for a one-way airport trip. Consequently, inequality has drastically increased, and while foreigners can enjoy, for example, dairy products or high-quality fish, many locals must find creative ways to keep starvation at bay.

They still keep up; Cuban sense of humour and their love to life is world famous. They tell me stories about ‘coleros’ (people, who would stand in lines early to have the best places and then to be able to sell it to others; and also used for people sleeping on trees and bushes to be able to get a good place in the line early in the morning) with a laugh. The question is, until when will this keep them going? For the time being, no political winds of change nor economic solutions are in sight.

” I love Cuba, but Cuba hurts,” I was told by a friend as a conclusion.