In 2016, Cuba’s government, which tightly controlled access to information and technology, set up state-run Wi-Fi hotspots across Havana. Whereas previously news, culture, and trends from around the world trickled in slowly, teenagers now had access to information, trends and ideas.

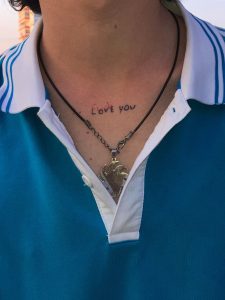

As most homes still don’t have internet, the teens gravitate to the city’s 35 Wi-Fi hotspots. Increased access to the internet has changed the ways that Cuban young people forge identities. Even back in the early 2000s, it wasn’t uncommon to meet a group of frikis (in the 1980s, French sociologist Michel Maffesoli coined the term „urban tribes” to describe small groups of people defined by shared interests and lifestyle preferences around which modern societies are organised) who took all of their cultural cues, sartorial and sonic, from a scratched Clash CD that they passed around and took turns listening to.

Broadband remains slow, and even the $2-an-hour charge at Wi-Fi hotspots can be too expensive for teenagers, so, they congregate and talk, not through machines but face-to-face, in public. On the broad boulevard of G Street or the Malecón, the waterfront promenade, or Paseo del Prado, or John Lennon Park, where they go to see and be seen. What do they do? Listen to hip hop, rap battle, record TikTok videos, take photos and videos for Instagram, skate and teach skating, dance, and talk.

These kids’ gathering is anything but political; they don’t seem to care about anything but their present. They are mostly coming from wealthy families, have relatives in the United States, or get their clothes in the black market; they look just like any other teen in the USA. They are organized in schools, the first person to organize the group will be the Boss. The Boss decides when and where they meet. They use encrypted WhatsApp messages. They chat, drink, skate, sometimes smoke pot. And they are already watched by the secret police. The reason is: they might be dangerous.

700 meters – it is the length on Calle G and Paseo del Prado where these kids usually gather. For them, 700 meters is the length of freedom and joy. In the future these 700 meters might be the place of change.

Books can be purchased here:

https://a.co/d/jgyhR2M

Main Publications:

Main Exhibitions:

FIRST HALF ‘23 | SUMMER GROUP EXHIBITION AT INDA GALLERY, 14 June 2023 – 1 September 2023

https://indagaleria.hu/en/exhibitions/148